Library News

The future of postcards

Posted on November 28th, 2022

The EIU Archives has a catalogue of thousands of old and new postcards from around Illinois, the United States, and the world that can provide insight into history, art, and culture not seen elsewhere. You can access many of them through the Booth Library online database, but to see the complete collection, one must come to the Archives in person.

By: Chloe S. Guiliani, EIU English major and senior

The 150th anniversary of American-made postcards is coming up on May 13, 2023, but the Golden Age of postcards are long behind us, ending over 100 years ago in 1915. Over the decades since, postcards have slowly fallen out as a popular form of correspondence. [1][2]

According to a 2017 article by Jeanette Settembre on the Market Watch website, with the rise of the Millennial generation and continued technological advancements, postcards have been cast to the wayside in favor of more convenient, instant communication. Historic postcard-publishing companies are shuttering, if they haven’t already; England’s oldest postcard publisher, J Salmon, halted their printing in 2017 and sold what remained of their stockpile throughout 2018. “Just 25 years ago more than 20 million postcards were sold each year, but now the number has dipped down to just five or six million.” [3]

With the prevalence of social media and reduction in the deliveries of physical mail that people receive each day, people today do not need to rely on postcards to communicate quickly or to capture vistas. Instead, we can easily take our own pictures and selfies on our mobile devices and choose whether to post them online, send them via text or email, or print them out. We can even edit and design our photos to look like a classic postcard, if we wish.

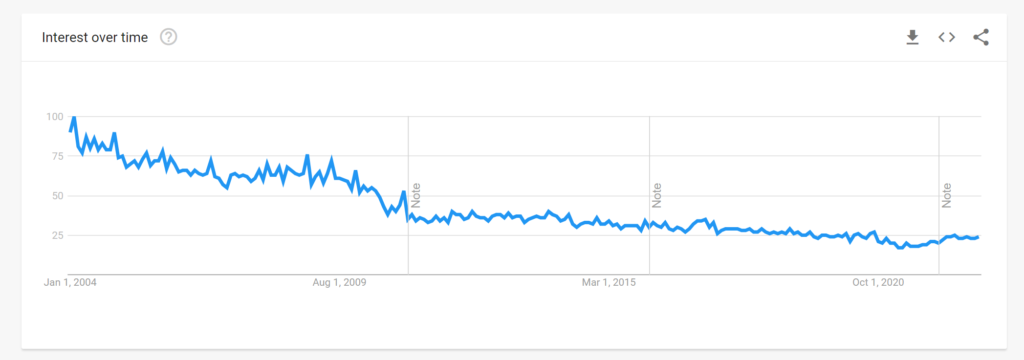

Plugging the term “postcard” into Google Trends will present you with the following graph, which seems to mark the slow downfall of the postcard in the digital age. According to Google Trends, which can track internet search terms from January 2004 to the present, the term “postcard,” to this day, has never reached the peak level of American web searches as it did in February 2004, with an interest value of 100. Currently, in November 2022, the interest value of “postcard” is only 24, which means that American searches for that term are down by 76% from its peak figure nearly 19 years ago. The interest value numbers look even worse for postcards when taking the Google Trends search worldwide, where the peak value of 100 was in December 2004 and is now only 5.

What then, does the future of the postcard look like outside the museum or archives? Do you remember the last time you received a postcard in the mail?

As a business, things don’t look bright, but the interpersonal exchange of pictures and short correspondence has not stopped. Looking to American-focused Google Trends again, it took only one year after the initial launch of the Facebook program in February 2004 for it to be searched for online more than postcards; the exact same can be said for Instagram, launched in October 2010.

Texting through SMS and MMS messaging has also exploded on the mobile market. In 2022, research points to 18.7 billion SMS and MMS messages being sent worldwide each and every day, which is a 7,700% increase in the number of texts sent over the past ten years. [5]

While the quick exchange of images and information will continue to grow and evolve, postcards as a medium to do so seem to slowly be going extinct, and if that is so, it will take archivists, researchers, historians, and collectors to preserve them as a flashpoint in the history of written communications.

Author’s Note: Chloe S. Guiliani is completing an internship this semester in the Booth Library University Archives and Special Collections.

Works Cited

- A History of Postcards. (n.d.). Seneca County, New York – The County Between the Lakes. https://www.co.seneca.ny.us/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Postcards-History-ADA.pdf

- Kentic, J. (n.d.). How Many Texts Are Sent Per Day? Modern Gentlemen. https://moderngentlemen.net/how-many-texts-are-sent-per-day/

- Postcard Collection – Essay, Appendix C: Manuscripts and Special Collections: NYS Library. (n.d.). Home Page: NYS Library. https://www.nysl.nysed.gov/msscfa/qc16510ess.htm

- Postcard – Explore – Google Trends

- Settembre, J. (2017, September 30). Postcards are becoming extinct and 5 other industries millennials are killing. MarketWatch. https://www.marketwatch.com/story/postcards-are-becoming-extinct-and-5-other-industries-millennials-are-killing-2017-09-30

My favorite postcard at the EIU Archives

By: Chloe S. Guiliani, EIU English major and senior

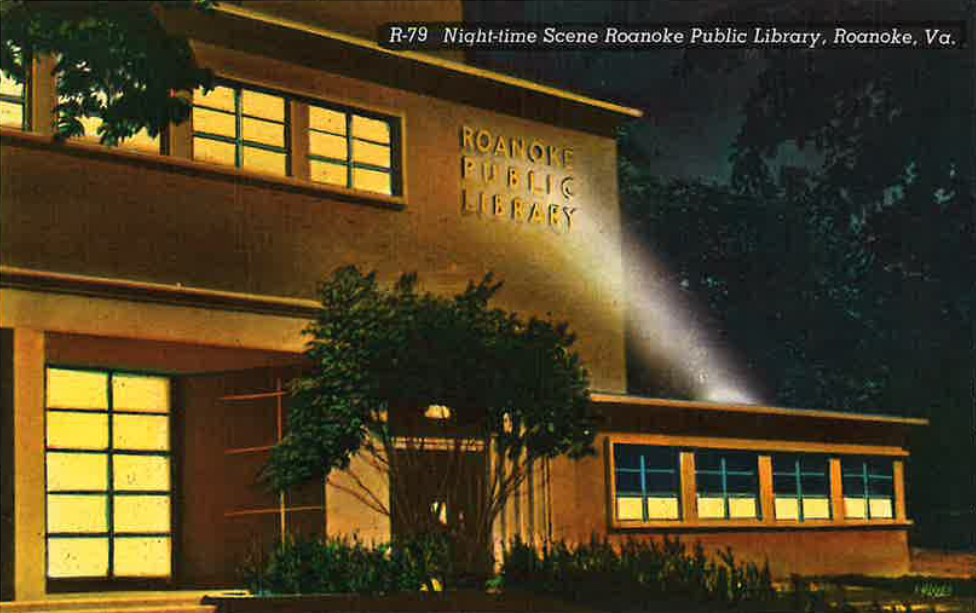

In all of my work at the EIU Archives, I hadn’t seen night-time views or inclement weather displayed on any of the postcards to which I was assigned. The views were predominantly of the daytime, where clear and sunny skies could lend to the design by lighting certain areas and casting shadows off objects or buildings. And even when it was obvious that the postcard displayed a winter view, the snow and barren trees were always picturesque and peaceful.

When I thought back on postcards I had seen in my own travels, I couldn’t think of any that stood out for weather or lighting reasons. Idealism is usually at the forefront of postcard design, since potential buyers are more likely to want postcards that capture “the best” an area or view can offer (and not necessarily what it looks like on the average day).

What first caught my attention with this card, in particular, was that it was a night-time view, but it wasn’t what kept me engaged. It seemed so low key compared to the “look at me, look at me” nature of most postcards. At the time of discovering this card in the archival collection, I was working on a project about “Lo-Fi” art, from audio and music to visual works, and what makes something “low fidelity.” Looking at the postcard, I thought to myself, “This has to be the first and only postcard I’ve ever seen that is a Lo-Fi artwork!”

It seemed as though the essence of the postcard was a typical view one might have of the library at night while walking on the sidewalk. It’s a very warm and inviting image, and as an English major, it makes me feel like there’s more of a story here. Just as a postcard might segue a person into reminiscing on an experience, the image pictured on this postcard made me think, “What happens next? What is the story behind this setting?”

And as someone with a knack for detail, there are certain efforts I see in this postcard that I have not seen in many (if any) others. From the way the light shines realistically on the “Roanoke Public Library” sign and doesn’t encompass every letter of it with brightness; or the way the foliage blocks the direct view of the door and matches the background foliage’s lighting technique, making the library feel surrounded by greenery (and it actually is, being situated in a city park).

I was also fascinated at how such a simply designed postcard could make the foliage look so well at night and highlight the silhouette of the background’s canopy, which contrasts with the subtly shaded night sky. Not only does the slight change in tint around the trees make the border between sky and tree more clearly visible, but it gives depth to the small amount of outer space depicted, and it shows that the rest of town is lit up, too (if we could only see past the foliage).

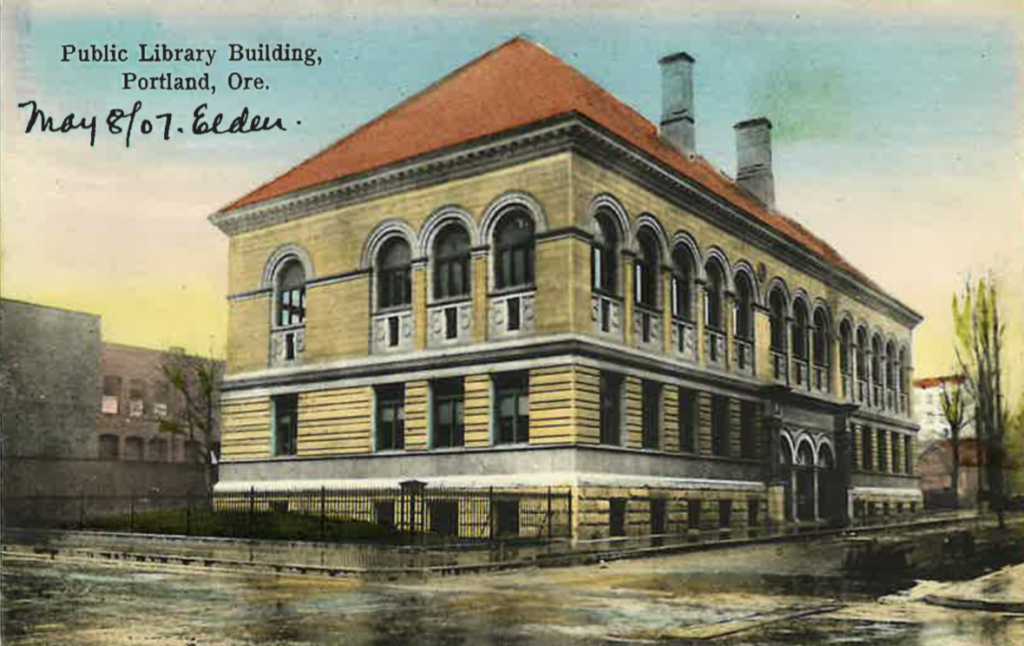

My runner-up for favorite postcard was a library view from Portland, Oregon. First, there are no other postcards that I have seen with such a watery sheen on the ground. In the design, one can also notice that the background is a rough U-shape of out-of-focus skyline, and that the actual focus of the foreground isn’t just the library building but the condition of the road in front of it. Considering the fact that Portland is a city with the third-most rain/snowfall in the entire United States, it only makes sense to not only have postcards with rain in them, but make that rain just as beautiful or omnipresent as it actually can be.

Author’s Note: Chloe S. Guiliani is completing an internship this semester in the Booth Library University Archives and Special Collections.

The craze of postcards: How they connect modern times to our shared past

By: Chloe S. Guiliani, EIU English major and senior

It may not seem that important to understand the origins of the postcard and picture-postcard, but postcards and their history not only give you an idea of what something looked like at a given time in history, but the history of human communication, the marketplace of ideas, and cultural exchange. In 1905, the Nottingham Sun was quoted in their report that postcards were “strengthening the bonds of international as well as individual friendship.”

They originated in the mid-to late 1800s, the time where the world was opening up due to the industrial revolution, and so, for the first time, people were able to send and receive messages and pictures from around the planet for as low as half the price of mailing letters in an envelope. For the people of that time, postcards acted like our modern texting, whereas letters would represent a phone call.

In fact, it was the opinion of many in that time that postcards would “ruin society,” whether they had pictures on them or not, just as we hear today about the linguistic effects — good or bad — that could come from texting or internet lingo becoming so commonplace. They argued then that with the limited space on a postcard, the result would be the ruination of polite conversation.

In addition, since most postcards weren’t in an envelope, they would lead to invasions of privacy amongst the population. This is still a topic at the forefront of much of society today, especially involving the privacy-encroachment that internet connection and social media bring us.

Though the picture postcard wouldn’t become a staple or craze until around the turn of the 20th century, advertisers had been inspired in the early 1870s to use postcards as “open announcements.” They were first restricted to written announcements, but the picture-variety arrived shortly after.

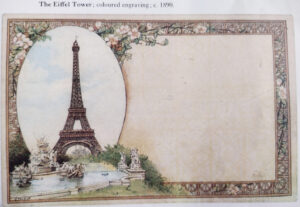

Impetus for the picture postcard grew at the Paris Exhibition of 1889, where the Eiffel Tower — just recently completed — acted as a major attraction for France. There, visitors could not only go up the Eiffel Tower but buy a postcard with its printed image and post it directly from the top of the tower. This trend caught fire and started the entire “postcard craze,” which spanned around the world from Paris to Vienna and the United States to Imperial Japan.

Subsequently, postcards became a hot item, and you could buy and post at the summit of whatever tower, lighthouse, road, or big and notable hill you happened to find yourself. Postcards were a quick and cheap way for our recent ancestors to capture and share an experience, and prove they’d done or seen it, whatever it may be, just as we modern people might make a social media post of a landscape or a selfie of ourselves whenever we happen to climb a mountain, reach a scenic overlook, or make it out of the grocery store in less than 15 minutes.

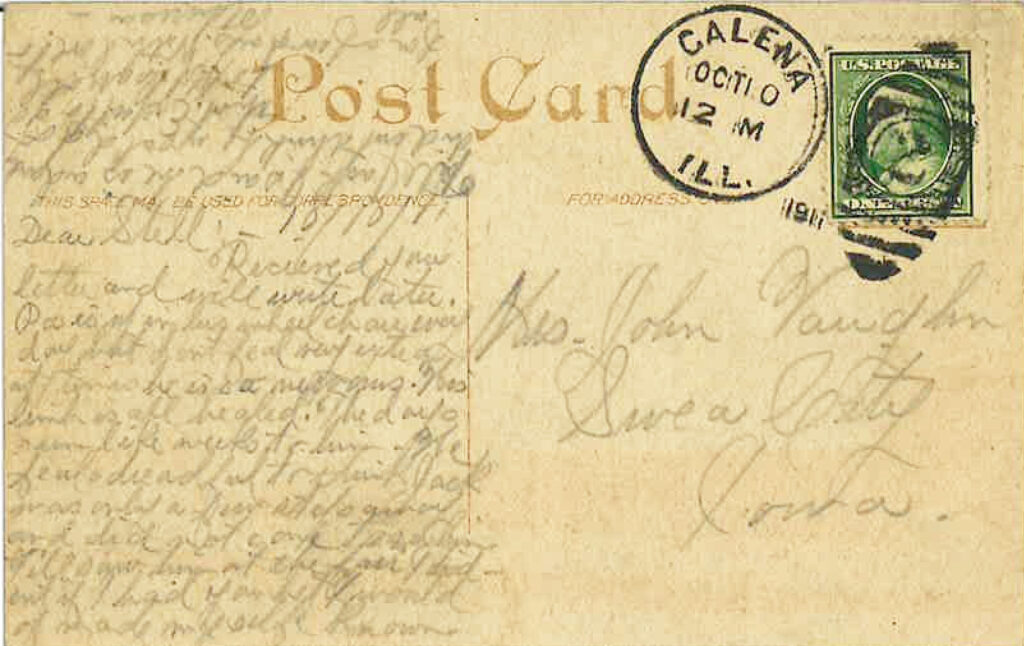

It might seem odd, but even the postmark over the stamp mattered, since it proved where and when you had sent the card from exactly, and collectors wanted it to match the location pictured on the card. This mattered so much, in fact, that many folks posted their cards to themselves. Not only that, but in France, you could take cards you never actually posted into the post office just to receive that valuable postmark, if only to get that gratifying feeling and prevent postmark FOMO. These historical “social media location filters” were valuable, not only to hobbyists and collectors then but collectors and historians now.

The entry to the EIU Archives is located inside the south atrium of Booth Library, by the clock tower. The 1972 second-edition Pictures in the Post: The Story of the Picture Postcard and its Place in the History of Popular Art by Richard Carline is available for checkout at Booth Library.

Works Cited

- Carline, R. (1972) Pictures in the Post: The Story of the Picture Postcard and its Place in the History of Popular Art. 2nd Edition. Philadelphia , PA: Deltiologists of America.

Author note: Chloe S. Guiliani is completing an internship this semester in the Booth Library University Archives and Special Collections.